Rocket Powered Bacteriophage

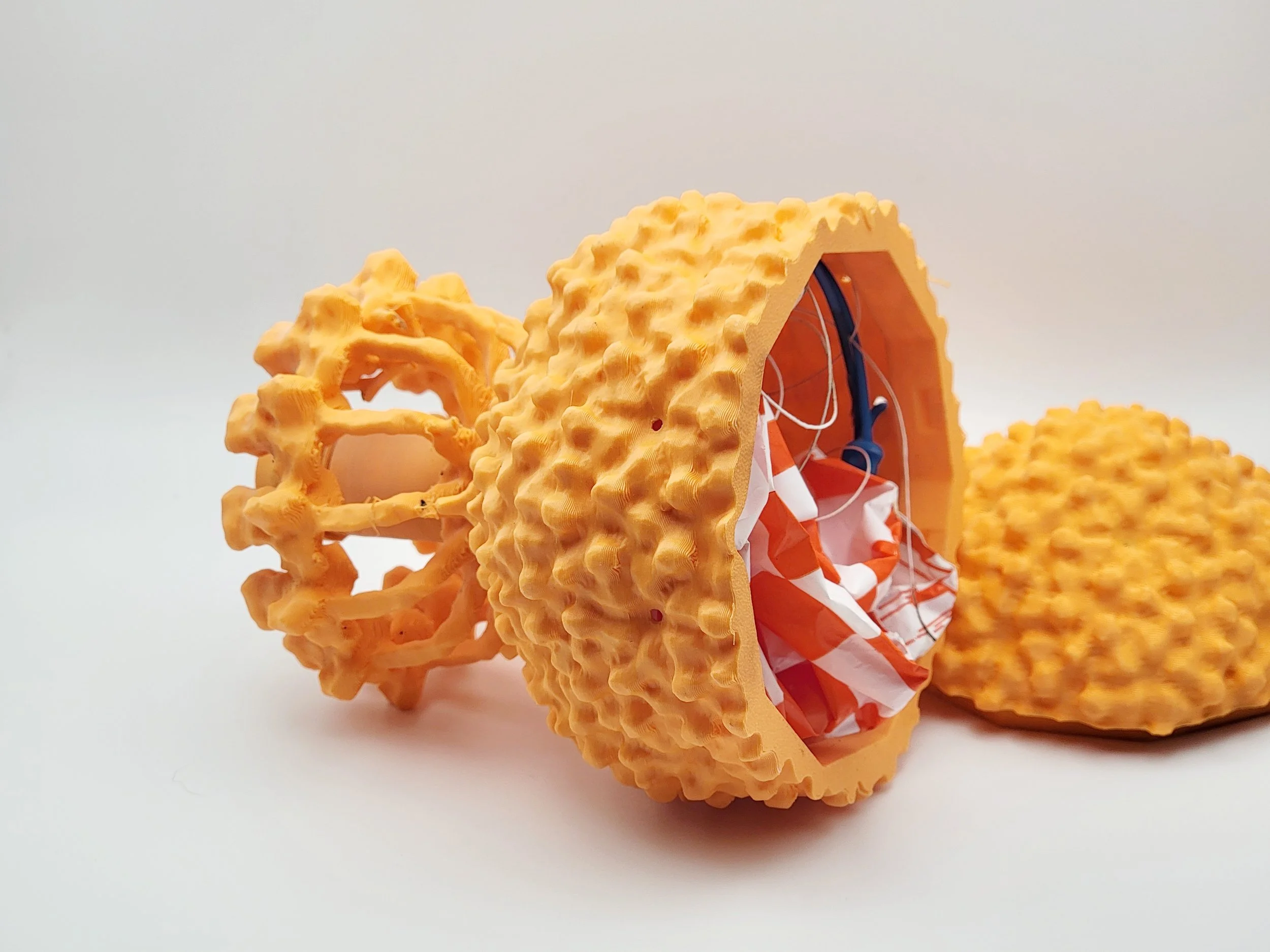

What started as a project to design a functional P68 bacteriophage container quickly evolved into something out of this world. My goal was to stay true to the original solved structure while incorporating a secure lid and closing mechanism. I designed two distinct models: one featuring a screw-based locking mechanism and another with a pop-top closure.

As I iterated through prototypes, I couldn’t help but notice its resemblance to the Apollo Lunar Lander. Naturally, the next step was clear—why not create the world’s first rocket-powered bacteriophage?

Iteration 1: Screw-Lock

To design a secure container, I started by importing the exporting the original PDB file into my favorite CAD software for editing. After cleaning up the mesh and down-sampling the vertices, I split the model into three parts for easier fabrication.

To ensure the container stayed securely closed, I incorporated six magnets into each half of the capsid head. I also added a threaded section to both halves. When aligned, these two pieces complete a thread that securely screws into the tail fibers. The end result was a functional, sturdy design that stays true to the bacteriophage's original geometry.

Iteration 2: Snap-top

After experimenting with a few prototypes of the screw-lock container, I decided it was time for something a little snappier—literally. Snap-top lids seemed like the perfect solution for quick access, but they came with their own set of challenges. The tolerances had to be just right: tight enough to stay closed, but not so tight that you’d need superhuman strength to open it.

To keep everything aligned (and avoid a wonky lid situation), I added a locating pin to ensure the top always snapped shut perfectly with the phage’s geometry. After some trial and error with the tolerances, I landed on a design that’s both secure and seriously satisfying to use (listen for the snap at the end of the build video!).

I had some translucent filament on hand so I quickly designed an LED holder and turned the model into a lamp!

A striking similarity to the Lunar Lander.

Here is where things get a little bit strange.

I placed my collection of phages on the bookshelf and stepped back. Two thoughts immediately went through my mind.

They look a lot like the Lunar Lander.

I NEED to put a rocket into it.

After all, scientists have put phages on rockets bound for the International Space Station, so why not flip the script and put a rocket on a phage?

Turning a phage into a rocket.

My graduate training was in lung and muscle immunology, not rocket science, so I was a little bit out of my wheelhouse here. However, I knew I had a few goals to get this thing in the air.

Reduce weight.

An Estes B6-2 engine can only lift 127g, but the model weighs 162g. Accounting for the engine itself, that leaves us with 110g to work with.

Add an engine mount.

Luckily the engines are easy to model and make a mount for. It’s just a cylinder with a hole on one end (for the parachute ejection charge), and a threaded cap. Once I made a quick mock up, I could combine it with the lightened P68 model and begin printing Phage Mk1.

Phage Space Program: Initial Launch

The stage was set. On one beautiful autumn afternoon I was ready to send this abomination of aerodynamics into the sky. However, after getting to the field I faced another problem: A launch pad. Normally, model rockets are guided up a metal rail, but this wouldn’t work for Phage Mk1. So I turned to the engineer’s handbook and used ole’ reliable: a roll of duct tape.

3…2…1…

Not a soft landing, but a successful launch!

The phage space program might have a chance!

Let’s try a second launch.

Rocket science is hard…

And for the blooper reel, here are two launches that could’ve been a better.

The aftermath.

A burnt parachute and a melted engine mount. Could’ve been better, could’ve been worse. Overall a resounding success.